I had just finished reading Ngugi Wa Thiong’o’s Decolonizing the mind: the politics of language in African literature when I went and posed a question on Afrobloggers’ Twitter and WhatsApp platforms. The question was simple yet thought-provoking. “When was the last time that you wrote more than half a page in your mother tongue” I poked.

It was a simple question that sparked a bigger conversation especially in the Afrobloggers WhatsApp group This question revealed a startling trend among the emerging African writers. Many could not write in their mother tongue and those who could, said they would not because it limited their reach.

Ngugi’s Perspective on Language and storytelling

Ngugi, in the book I mentioned above, explains why there is a need for the African writer to go back to writing in the mother tongue. “If in these essays I criticize the Afro-European (or Euroafrican) choice of our linguistic praxis, it is not to take away from the talent and the genius of those who have written in English, French, or Portuguese. On the contrary, I am lamenting a neo-colonial situation which has meant the European bourgeoisie once again stealing our talents and geniuses as they have stolen our economies. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Europe stole art treasures from Africa to decorate their houses and museums; in the twentieth century, Europe is stealing the treasures of the mind to enrich their languages and cultures. Africa needs back its economy, its politics, its culture, its languages, and all its patriotic writers.”

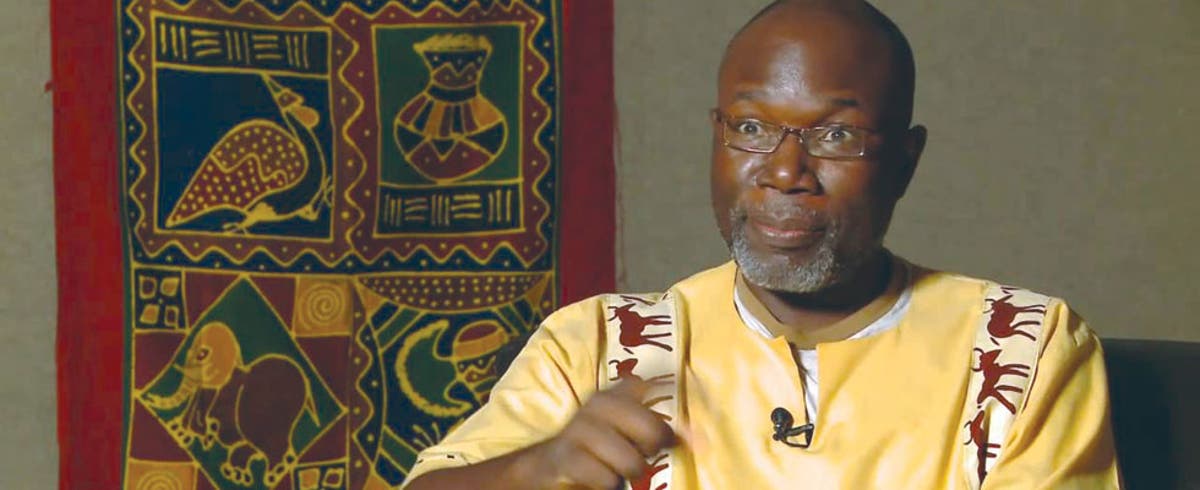

Ngugi also commented in one of his interviews that he foresees an Africa where “We shall write in African languages, we shall invent in African languages, African languages will be talking to each other.” This seems far from becoming a true dream in our lifetime where many writers are clamoring for attention and influence, such that they feel using their vernacular would limit their reach. However, all is not bleak as the roots of Ngugi’s thoughts are already being fully supported by some veteran authors in Africa. One such Author is Zimbabwe’s Ignatius Mabasa who was awarded a Ph.D. for the first-ever thesis written in ChiShona at Rhodes University.

Ignatious Mabasa is a renowned Zimbabwean author, filmmaker and storyteller whose language of expression is Shona, a vernacular for the majority of Zimbabwe’s population. He like Ngugi Wa Thiong’o reiterated the importance of using our own languages to tell our stories by saying: “The choice to use ChiShona is a response to the exclusion and marginalization of othered knowledges. By using the Shona language, I am rethinking pedagogy and targeting a disenfranchised audience. Brutal colonial conquest and forced acculturation have disturbed and created insecure conditions for Africans. Africans have had other people tell their stories for them – othering them, judging them, labeling them, misrepresenting them. My thesis in Shona is part of unthinking Eurocentrism and searching for alternative epistemologies. The African cannot continue thinking as if he is still living in a colonial world, perpetuating colonial discourses and perspectives.

“Profound!

The dilemma

Language plays a critical role in our storytelling as African writers and bloggers. Of course, some may argue that they want to reach a wider audience but the fact remains that certain stories cannot be told with the same adequate nuance using borrowed languages.

We must also remember that Ngugi is not the only one to emphasize the impact language has on people. Frantz Fanon in his book Black Skin, White Masks says “…To speak means to be in a position to use a certain syntax, to grasp the morphology of this or that language, but it means above all to assume a culture…”

The dilemma therefore which falls on the lap of Africa’s emerging writers is: To adopt foreign languages and appeal to a larger audience at the detriment of erasing their own cultures, or to follow in the footsteps of literary giants like Mabasa and stage a revolt challenge against “gatekeeping in academia where research and the language marginalizes certain classes, creating dangerous dominant narratives and pseudo-realities?”

How do we appeal to a global audience while managing to retain our own cultures? Is it possible to tell our stories with enough nuance using foreign languages? Can we heal a sickness within the same confined environment that caused it? Food for thought.